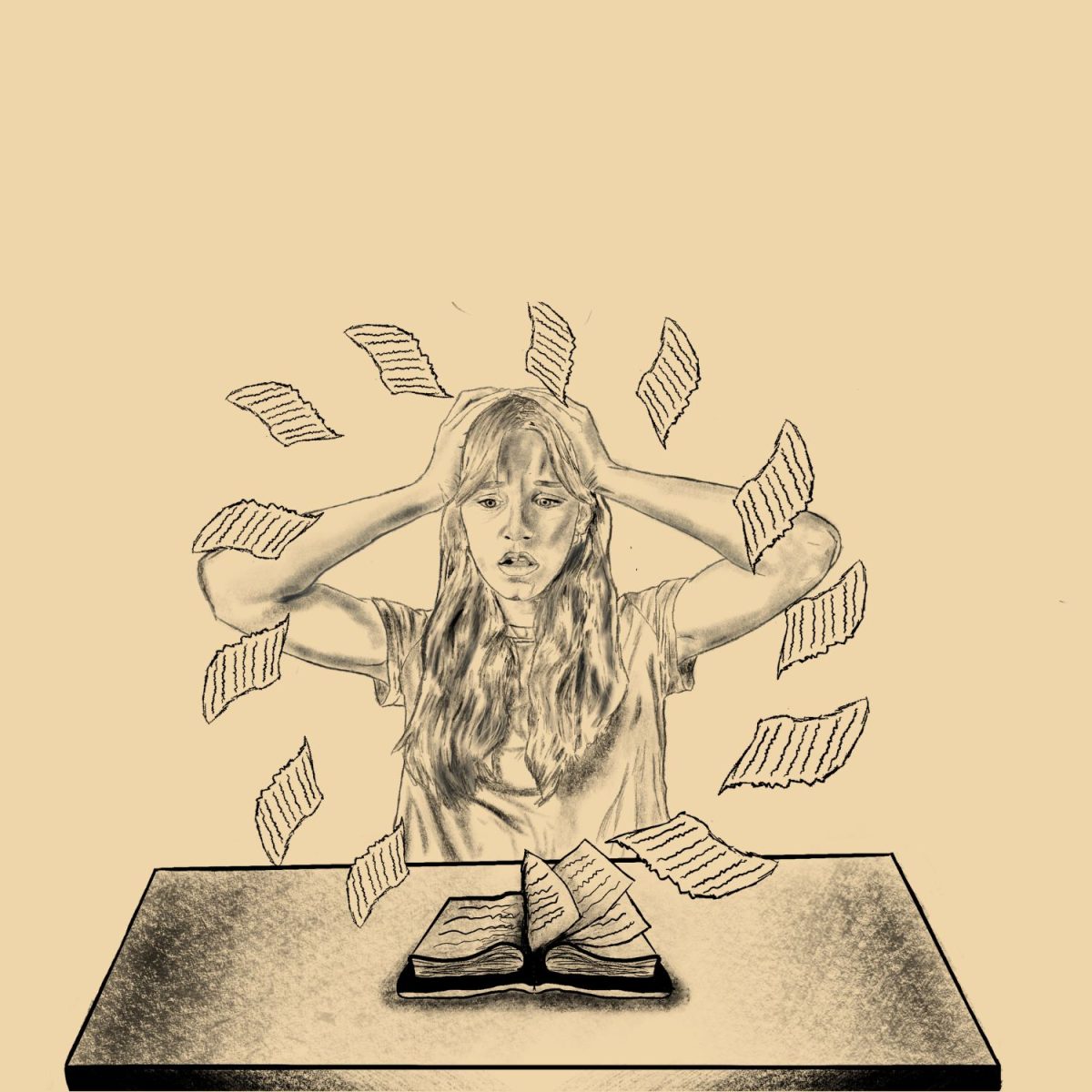

A single drop of sweat follows the curve that is a soon-to-be-jawline. It falls through the air before hitting the ground and joining the other drops in a puddle. Clenching the five-pound weight with both of his hands, the scrawny 15-year-old boy’s arms shake as he starts to count to 20. Holding the weight over his head, the borderline pre-teen drops the dumbbell before he can even reach 10 seconds. He grabs his shoulder and squeezes as his breathing slows and pain radiates throughout his arm. Many adolescents fail to research the effects of weightlifting before beginning training, leaving themselves unaware of the possible harm on their bodies.

The stress of lifting, ranging from leg exercises to bench presses, can continuously put stress on the epiphyseal plate, more commonly known as the growth plate. These plates are found at the end of long bones and supply the cells needed to produce bone. Putting stress on these plates is the main danger of lifting, especially for teenagers. When teenagers have not reached all levels of physical maturity, they are left vulnerable to long-term damage because any stress can affect the complete growth of the long bone. Once matured, growth plates are less susceptible to damage and cannot affect the long bone’s production.

“Approximately 15% to 30% of all childhood fractures are growth plate fractures,” the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons found. “Because the growth plate helps determine the future length and shape of the mature bone, this type of fracture requires prompt attention. If not treated properly, it could result in a limb that is crooked or unequal in length when compared to its opposite limb.”

Stigmas attached to “getting ripped” to exceed in sports usually relate to teenagers directly. As middle schoolers arrive in high school, they unwillingly trade being the largest in the hallways for barely being able to see over the desks. Their minds are automatically programmed to believe they need to look like a carbon copy of Arnold Schwarzenegger to get picked for the team or even score a date to prom. What is giving them these false ideas, however, is that many upperclassmen gained natural muscle over past years from playing sports, which fuels insecurities in others. Some young teens begin to push themselves past their natural limits and put themselves in danger as they start to lift weights without knowing the consequences.

“Students need to be careful not to hurt themselves,” school nurse Darlene Vargas-O’Connor said. “I would advise students to always resort to forms of gaining muscle other than weightlifting because of the negative effects. The possibility of muscle strains, as well as other injuries, are very dangerous, and students need to beware of the possible damage to their bodies.”

Many of the harmful effects of weightlifting can be prevented. Stretches can stop the many risks that weightlifting brings. Simply taking five minutes before lifting to stretch reduces the likeliness to pull a muscle or damage growth plates. When stretching before lifting weights, the amount of muscle soreness post-workout will also go down. The Journal of Athletic Training found a decrease in muscle soreness when testing on military trainees under their protocol for stretching. In 72 hours, trainees being tested could feel a reduced amount of soreness from the stretching that was implemented before and after working out. This study applies to not only military weight training, but any person lifting. Reserving a couple of minutes before lifting can allow for a completely different outcome of training.

For stretches before lifting weights, click here:

Another primary factor in the dangers of weight training is age. Being too young or too old can make the training risky, putting many early high schoolers in danger. Starting to lift weights before completing the final stages of puberty is dangerous and not proactive. Teenagers undergoing puberty will not see dramatic shifts in body composition when lifting because of the vast changes their bodies are still facing. Since puberty usually ends earlier for females, it is safer for girls to lift weights earlier than males, who should start at the end of their puberty process. Because of the waiting period to start lifting, the best way for early teenagers to gain muscle mass while still being safe and healthy is strength training. Body weight training includes push-ups and pull-ups, as well as other forms of resistance training.

For types of strength training, click here:

https://greatist.com/fitness/50-bodyweight-exercises-you-can-do-anywhere

“[W]eightlifting is distinct from common strength training because it involves specific types of rapid lifts,” that can possibly cause injuries; however, “[a]ppropriate strength training programs have no apparent adverse effect on linear growth, growth plates, or the cardiovascular system,” according to the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness.

Overall, weightlifting allows for rapid growth of muscle mass compared to other forms of exercise, but injuries can occur more frequently. Other options for workouts include strength and resistance training, which have a reduced amount of possible damage on teenagers’ bodies. If you are thinking about trying weightlifting, you may want to weigh in on the consequences before causing permanent harm on your body.