The word “Marzano” has been thrown around a lot lately. Students are ushered to the gym and forced to participate in strange surveys in the name of Marzano. One can no longer walk into a classroom without anticipating being asked to rate their understanding on a Marzano scale. But what exactly is this bizarre thing called Marzano?

According to the Marzano Research website, the program focuses on student achievement in the classroom. It is meant to show better ways to teach and improve education. The program is based on 5,000 studies and is meant to “[help] teachers intentionally plan for and teach rigorous lessons, reflect on their progress, collaborate with peers engaged in the same work and monitor their students for the desired results.”

Besides the surveys and the scale that rates student’s understanding, there are other ways Marzano is changing the classroom. Students should not be surprised to see teachers coming into classrooms and rating other teachers on the way they’re performing Marzano activities.

“If you’re a teacher that says, ‘Hey, Ms. Weber, I need help with implementing scales in the classroom, can you come in and just watch me on this day?’ I come in and I can give you feedback that will never actually go to the administration,” communications dean Angela Weber said. “[It’s a] non-threatening way of getting peer feedback.”

Implementing Marzano standards begins with a three year process. This year marks the first year, which is the most intense year, involving training of the entire faculty. Each subsequent year provides more flexibility to implement the rules the way the faculty sees fit.

“In the beginning of this year, the teachers may have had apprehension because it’s something new, as we’ve moved through the process it has become more positive,” Assistant Principal Corey Ferrera said. “We have a great staff here, our teachers want to do anything that benefits our students. This process has gotten the teachers talking, working together. Now we have teachers going into other teacher’s classes and watching them teach. That’s great because were all learning and growing together.”

Marzano standards are aimed at increasing the rigor in classrooms. Educators are trained to get students into deeper thinking with cognitively complex tasks. This means that teachers will act as a facilitator and guide as students engage in independent learning. Students use tools such as the Marzano scale, which acts as a road map and a way for students to check their progress.

“Marzano is about intentional instruction, nothing in a class is haphazard, everything is planned with student achievement in mind, there is a lot monitoring of students by the teacher,” Ferrera said. “Kids are in groups working collaboratively and the teacher is the facilitator. We want students to sometimes struggle with the content, but the end result being that they have a better understanding of the content.”

Administrators and Marzano committee members perform observations in different classrooms. They look for 41 different elements that make up an effective teacher. When teachers rate each other, they are ranked in multiple Marzano categories, like “provides rigorous learning goals.” Teachers can receive a rating of either beginning, developing, applying or innovating in each category.

“[The Marzano committee] represent the various arts and academics on campus. We are learning to be mentors or peer teacher[s] so we can help assist our colleagues in different aspects of Marzano,” Weber said. “For example, if they need assistance or want somebody just to come in and observe their classroom while they’re implementing scales or they want to try different kinds of rigorous teaching of different content then [we] have been in training to be able to assist them in that.”

Another goal of the observations is to facilitate more positive relations between administrators and students. Students are meant to see administrators in their classes more often and know that they are there to meet the students’ educational needs.

“I have seen positive outcomes with Marzano. If there’s anything that we can do as educators to possibly raise student achievement, we should give it a shot,” Ferrera said. “It’s ultimately about the students and you being ready to leave high school. Marzano is a tool. Is it perfect? No, nothing’s perfect but we learn more everyday.”

However, not all opinions of Marzano are positive. When The Muse staff asked teachers for their personal opinions on Marzano, many of them refused to comment. Some students, on the other hand, are more vocal about their feelings.

“Marzano can be effective in some situations, but personally I feel that it’s being way over-implemented,” strings junior Emily Winters said. “Teachers already have their own systems and stopping all the time to rate yourself wastes time. A lot of students actually lie about what rating they are in order to keep the class going.”

Some students believe that Marzano’s standards and classroom practices discourage independence in the classroom, and that Dreyfoos students have shown they are able to learn without the program’s element of hand holding.

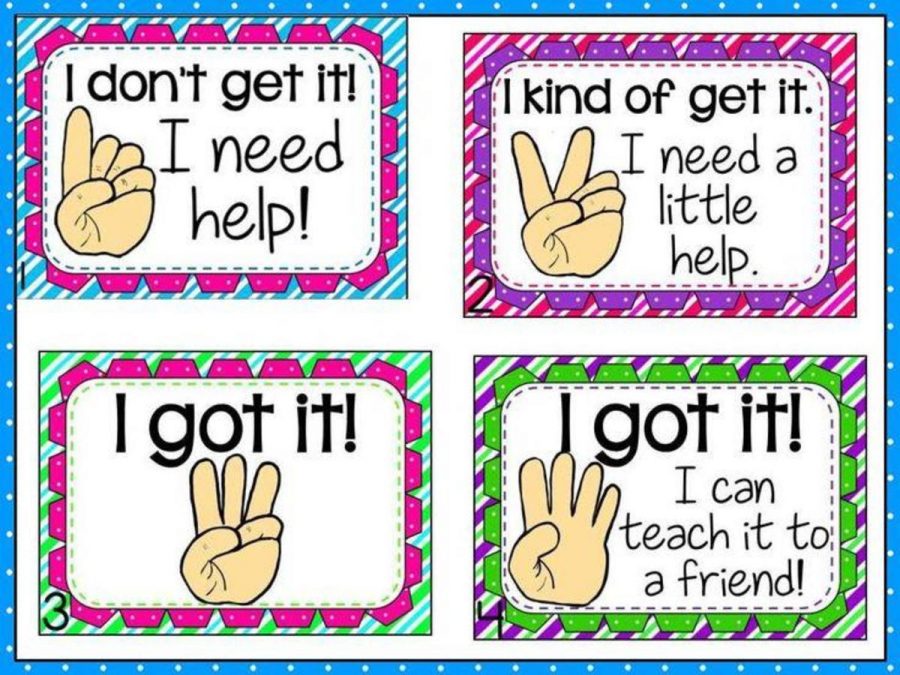

“I think that the concept of a set of best practices for teachers to use in the classroom is a good idea. However, I don’t think Marzano is really what we need at Dreyfoos. I think that we’re being taught to be dependent rather than independent when our teachers ask us to hold up a hand signal that corresponds to how well we comprehend the material,” communications alumna Shane Meyers said. “As a [former] senior AP student, I feel that I should be required to take the initiative to raise my hand or approach my teacher after class if any of the concepts aren’t clear to me. No college professors will be using the scale system to baby their students through their curriculum, so there’s no point in having our AP teachers use that system now.”

A popular discussion is the differences between Marzano and Common Core, another program which sets academic standards. Robert J. Marzano, the founder of the program, has written several books and spoken for Common Core. While Marzano and Common Core share similarities, such as a focus on academics being applicable in the real world, it is important to remember that Marzano was created off the research of 5000 studies, and Common Core is only one of those studies. Therefore, Marzano is a combination of the strongest of parts of previously existing programs.

“I’ve read the books that Marzano has written and I feel that what he is doing is he is taking the best practices of the past thirty years and packaging it into a new way,” English dean Richard Ehrlich said.

There was initial hesitation from the Dreyfoos faculty to adopt something new. Marzano standards at first seemed mysterious to both teachers and students alike. As the year has moved on, educators have taken bigger steps to implement Marzano standards.

“There actually [are not] a lot of new things in Marzano but actually it’s taking what works and using it in a way other people can digest. If people choose to use the method, great! What it comes down to is that the teacher knows their methods best,” Ehrlich said.

One of the largest tools implemented into classrooms are the use of scales. These are rankings of student comprehension from one to four. Student self rank themselves at multiple steps during a learning activity. A one signifies no understanding, a two signifies a partial understanding but requires further assistance, a three signifies understanding and a four signifies mastery and the ability to teach others.

“I will always tell the students the objective. The objectives tend to be [written with jargon] and we talk about what it means in everyday language,” science teacher Marilyn Howard said. “What I’m doing differently than other teachers is after we talk about the concepts and then have the students write down what they think it means in everyday words. They go back in and fill out [the scale]. It helps students to organize their thoughts.”

Mrs. Howard’s students gave overwhelmingly positive reviews for her interpretation of the Marzano program.

“Mrs. Howard has implemented her version of the Marzano scale in AP Chemistry, by passing out charts that we fill out after each lesson. Each lesson is divided into smaller topics on the chart that we then fill out based on what we remember from the lesson,” piano senior Laura Bomeny said. “This has been an effective study tool, in my opinion, as it helps us to remember the most important details of what we need to know for the test.”

Teachers learn these skills during meetings. These occur on a monthly basis and consist of LTM trainings and Professional Learning Community (PLC) meetings. At these meetings teachers work together with administration and Learning Science International (LSI), a company run by Marzano, and learn the Marzano guidelines and how to implement them. Each teacher is given an iPad and taught about a different aspect of Marzano through an online tool. Teachers then visit classrooms to observe other teachers and discuss what they saw with a Marzano trainer.

“Marzano is an effective tool, but that’s what it is, a tool,” Ehrlich said. “Teachers need to decide for themselves whether it works or not. Working with the students, and together, we find the right path.”

Marzano has made controversy across the nation and here at Dreyfoos. There has been some resistance and hesitation to what many feel as a “regimented” way of learning.

“I believe that Marzano shifts the goal of school from learning to grades. It causes students to be more focused on their grades than understanding,” communications sophomore Garrett O’Donnell said.

Marzano is linked with the Common Core State Initiatives, of which 44 of the 50 U.S. states, including Florida, have passed. Common Core is aimed at creating standards for national education. Common Core only covers mathematics and English language arts.

“I believe in impression of education which is more creative where students experiment and create and share ideas. Marzano takes that away and creates rigidity.” physics teacher Michael Rathe said. “I am more than just a teacher of physics. I think teaching is more than just materials. Its an art of communication to get kids to share ideas. I want to teach kids. I don’t want you to just spit back information. I don’t want robots.”

Marzano isn’t anything original, but it’s certainly making waves at Dreyfoos. Schools are constantly trying out new academic programs, but whether the programs will be successful is a question only time can answer. For now, students will have to endure the scales and surveys and pray that it will all pay off in the future.

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)