On any given school day, students may notice security monitor Mihail Chira driving a golf cart across campus, making sure doors are locked, buses have arrived, and students are wearing their IDs. To many, he’s simply one of the school monitors patrolling the campus. However, behind the driver’s seat is a man with a story that stretches from the classrooms of Moldova to the walkways of West Palm Beach.

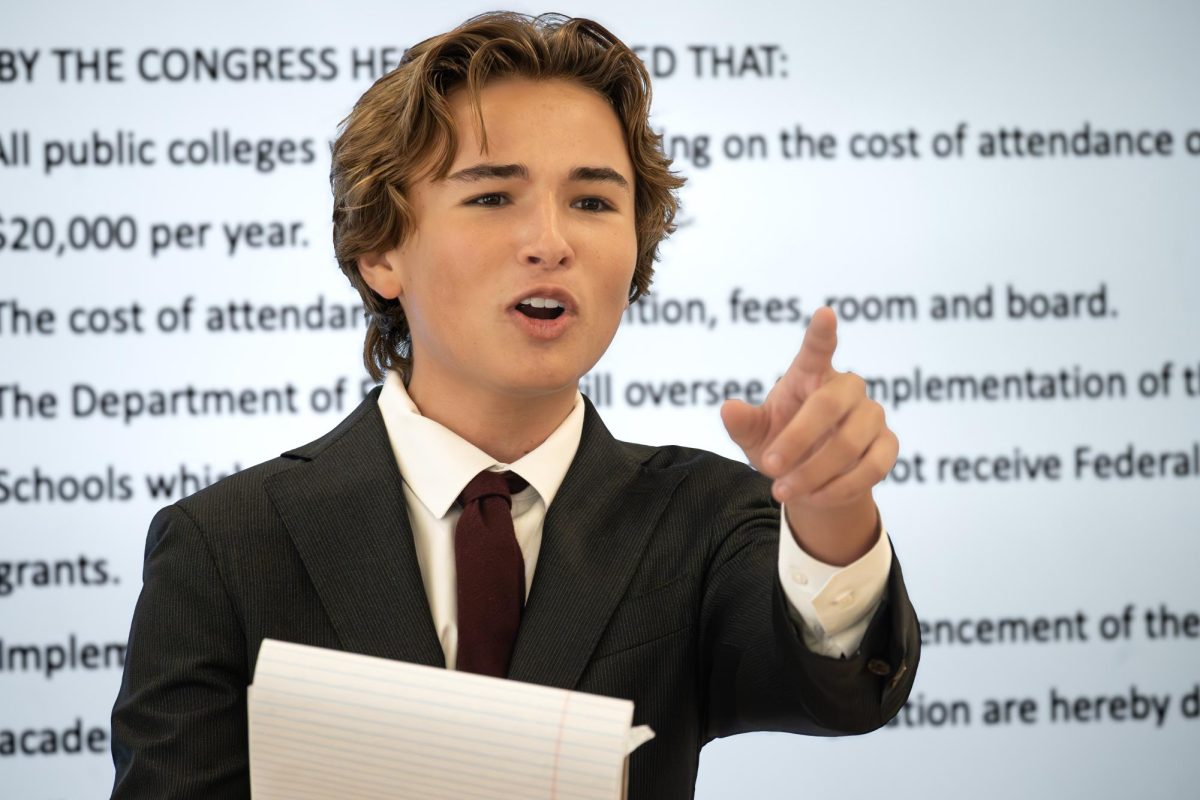

Growing up, Mr. Chira had an innate attraction to debate. However, due to pre-existing social and political systems in Moldova at the time, he was unable to pursue it. Moldova, a small Eastern European country nestled between Romania and Ukraine, spent much of the 20th century under Soviet rule. Activities like debate were discouraged in schools, since open argument and free expression were seen as challenges to the state’s authority, specifically the communist ideology.

“Of course, I would have loved to debate if I had the possibility at the time,” Mr. Chira said. “It’s great to learn how to argue with somebody, to prove something. Debate sets students up for success.”

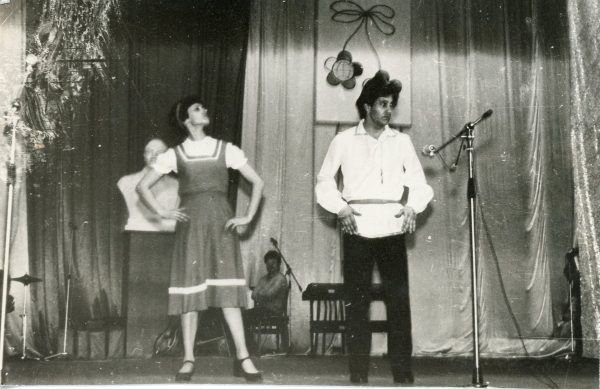

Despite currently working in the security sector, Mr. Chira first worked as an educator. His career began in 1982, when he became an English teacher at Prometeu ProTalent, a high school in Chișinău, Moldova.

“My family were all teachers: my parents, my wife’s parents, my sister,” Mr. Chira said. “I wanted to follow in their footsteps.”

His classrooms buzzed with the sound of pages turning and chalk scratching across slate boards. Posters of English vocabulary terms and charts shared space on the walls, while stacks of student papers covered wooden desks.

Mr. Chira’s goal of providing students with “leadership” and other public speaking skills came alive in 1994, when he and his wife introduced a debate class to the school, aiming to provide “something new for the students.”

“I started a debate class, and from there we built a connection with a school in Pennsylvania,” Mr. Chira said. “The kids went to classes, and there were different activities. They would see our school, and we would see theirs.”

What followed was a series of international exchanges that gave his students a chance to spend time abroad further developing their leadership skills that come with it. The Youth International League program expanded into a three-year cycle: the first year in Washington, D.C., the second in Europe, and the third in England.

“The Youth International League program helps to teach students how to become leaders, and now, the kids are all over the world,” Mr. Chira said.

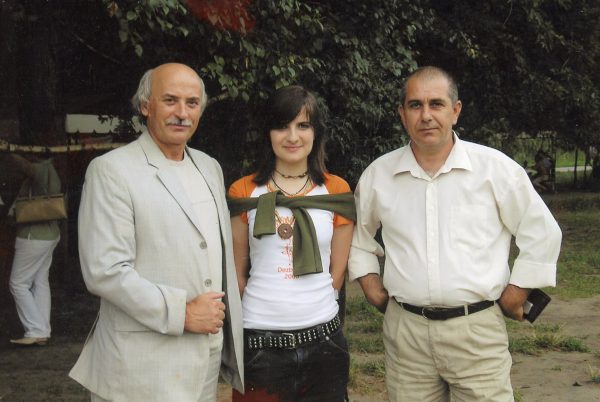

Mr. Chira not only taught his students leadership skills, but instilled personal lessons to his family. His daughter, Diane Chira, who worked as a chemistry teacher at Dreyfoos for 11 and a half years, remembers various messages from her father.

“My father always makes sure that I remember that other people’s needs are just as important as mine and to make sure that I take everybody else into consideration when making decisions and choices in life,” Diane Chira said.

Ultimately, Mr. Chira decided to leave Moldova in 2013 after 31 years of teaching, a choice fueled by his and his wife’s desire to be close to family. Upon moving, his wife found a job as a counselor at Suncoast High School, and Mr. Chira continued his search for a job.

“Being in Pennsylvania (for trips) prompted me to come to the U.S.,” Mr. Chira said. “I was already familiar with the school system and the people here, so the transition was not difficult.”

Mr. Chira’s first job upon immigrating was as a substitute teacher in Port St. Lucie for four years, later coming to our campus in 2021. The school’s environment was distinct from the classrooms he had known in Moldova: hallways carried the sound of music scales, paint dried on canvases in the art studios, and lines from rehearsals resounded from the stage.

“What I like about Dreyfoos is that the kids and teachers are special,” Mr. Chira said. “There’s always something happening. Nobody pushes you, you do it yourself, which makes it special.”

Media specialist Edward Hornyak worked with Mr. Chira for three years during his time as a substitute.

“He was very friendly with the students, and when he was in the media center, he managed multiple classes at once,” Mr. Hornyak said. “He did a very good job.”

Mr. Chira worked as a substitute until 2024, when he made the transition to a security monitor. Being a security guard gave him a different kind of responsibility: protecting the school community while still interacting with young people, something that remained prevalent in his work.

“In general, (being a security guard) is a permanent job that I don’t get from being a substitute,” Mr. Chira said. “I like to take care of the students, make sure they wear a badge, don’t go outside, don’t jump over the fence,” he said with a smile.

Now, one year into being a security guard, much of Mr. Chira’s work is done from his golf cart, which has become part of his daily routine, a distinct change from the classroom setting he had grown familiar with.

“I started driving the golf cart from the third day of my work (as a security guard) here because the first day I made 65,000 steps,” Mr. Chira said with a laugh. “It is helpful when I need to move from one side of campus to another, and if somebody’s calling me, I have to move fast.”

Throughout his career, Mr. Chira has taken on a variety of roles, beginning as a teacher in Moldova, later serving as a substitute after moving to Florida, and most recently working as a security monitor.

“I’m sure that he has changed in a lot of ways, but they (his past positions) all have one thing in common, and that is interacting with young adults and children, which has always been his passion,” Diane Chira said.

When asked how he would like to be remembered, Mr. Chira didn’t hesitate.

“Like a good human being,” he said with a smile.