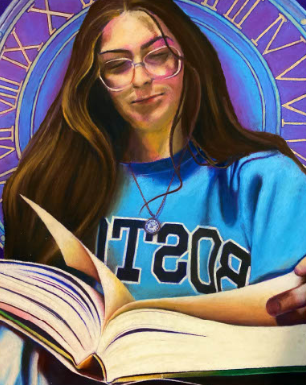

Visual senior Riley Shea received a perfect score on her Advanced Placement (AP) Drawing portfolio, but she doesn’t think she deserved it.

On Sept. 18, 2023, The College Board notified Shea by email that she was a part of the marginal 1.36% of students internationally to obtain every point for the exam, and the only student at the school to achieve the accomplishment that year.

“I’m not perfect at art,” Shea said. “Looking back at it, I’m like, ‘Man, how did they give me that?’ Maybe I should have gotten a five, which I did get (…), but I have no idea how I got a perfect score.”

According to UWorld, an online education platform, most high schools and colleges around the country recognize The College Board’s AP program as a benchmark for testing a student’s academic abilities at a university level. The College Board’s AP visual arts classes and AP Music Theory class allows them to assess creative disciplines alongside more traditional ones. While exam scores for academic classes are strictly based on whether an answer is right or wrong, the nature of art courses means how well a student performs on the exam may be affected by subjectivity.

“People have emailed me, and they’re like, ‘Why’d I get this (score)?’” AP 3-D Art and Design teacher Marcela Ramos Castillo said. “I have to tell them (the students) that the people that look at these have their own tastes. For this group, they just happen to feel this way, and it sucks, but that’s the problem with trying to put some kind of numerical value on something that is as subjective as art.”

The College Board’s visual program is divided into three courses: AP Drawing, AP 2-D Art and Design, and AP 3-D Art and Design. While each class varies in artistic mediums, they share similar formats for the end-of-year portfolio that all students submit and the rubric that they are all assessed on. These factors differ from the more conventional multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and free-response questions (FRQs) used in the majority of other AP classes and their respective exams.

“I balance having to stick with the rubric in an AP class along with my more holistic, personal view of art,” Mrs. Ramos said. “If (you’re making) something you’re passionate about and interested in, there’s value in that. I try and put myself and The College Board out of that equation, and my suggestions would be more about, ‘Okay, how can we get closer to expressing the thing that you’re trying to express?’”

According to the Art of Education University, in 2019, the AP Art and Design program underwent a major reconstruction. Previously, art was scored on “breadth, concentration, and quality,” and around 24 pieces were submitted. But now, students are judged on their development of a Sustained Investigation, an in-depth visual exploration of a common concept found throughout 15 of their creations, accounting for 60% of their total exam score. Selected Works, the other portion of the exam, consists of another five pieces that demonstrate their strengths.

“When I first started teaching it (AP Drawing), it was like students were making work for a final exhibition,” AP Drawing teacher Ryan Toth said. “Now, they (The College Board) want to see your studio visit. They want to see how you think. They want to see your process. Then, they want to see a little bit of your exhibition. They want to see how everything is made.”

Like the AP Art and Design program, the AP Music Theory course, taught by music dean Stefanie Katz Shear, prioritizes the process rather than focusing on the outcome, emphasizing a deeper understanding of musical elements such as rhythm, melody, harmony, and form. The final exam includes 75 MCQs, including questions in which students listen to music and match the corresponding notes played, but the majority of a student’s score (55%) comes from the FRQs. Piano junior Josefina Ezcurra said that when she took the class as a sophomore, the most difficult aspect of the exam for her was sight singing, the portion where a student has 75 seconds to examine a melody they have never seen. Then, they record themselves vocalizing it and submit it to the Digital Audio Submissions Portal.

“At first, I actually thought it (AP Music Theory) was very easy for what it was,” Ezcurra said. “But it got hard very quickly because it’s a detail-oriented course, and there’s a lot of things that you might miss if you’re not paying attention to what you’re doing in the class.”

Strings sophomore Mia Martinez, who is currently taking the class, said that although the AP Music Theory curriculum helps students in trying to understand different parts of music, “it doesn’t really play into actual musical skill.” She believes the class is “subjective” in its judgement of a student’s comprehension of the art because the course focuses mainly on 18th century classical music, and she thinks that “even though they (the techniques taught) were followed back then, no composer today is going to follow any of those rules.”

“I think it would be really nice (to learn more about different musical genres within the class),” Martinez said. “It is cool to understand the more rigid structure of music if you’re just getting into composing, but since we don’t follow that as much anymore, it would be helpful (to change the course) so we can apply it to new genres and what we’re actually playing.”

On the other hand, Ezcurra thinks the class does effectively ensure objectivity with how the curriculum is set up; she said it enables students to better grasp the fundamentals of music because of its structured approach, allowing for skill-building in the many elements that compose music theory.

“It can definitely help with the way you perceive your (musical) scores and help you engage your thoughts while listening to music because you can find more different, specific things (within music),” Ezcurra said.

AP 2-D teacher Scott Armetta said that the visual classes lack the structure found within the AP Music Theory curriculum that makes AP Music Theory, according to Ezcurra, inherently more objective in the way the final exams are scored. Mr. Armetta has taught the AP 2-D course for over 20 years and recognizes the role that opinion plays in the evaluation of his students’ art portfolios, a problem not faced in other AP classes.

“It’s not as objective as an equation or even history where you can defend a position,” Mr. Armetta said. “I always try to let students know as much as possible (that art is subjective), so (I tell them to) ‘make the work you want to make.’”

Unlike traditional AP tests where students cannot ask their teachers for advice before they submit their answers, visual teachers are able to guide students through the process of revising their pieces before turning in portfolios. In fact, this is heavily emphasized by The College Board in their course descriptions, as they state that part of the students’ scores will be based on their “sustained investigation through practice, experimentation, and revision.” Mr. Armetta pointed out that in his opinion, The College Board’s encouragement of these practices pushes students to take risks and explore within their art.

“Not necessarily every attempt at working within the Sustained Investigation is going to be as successful as you hoped,” Mr. Armetta said. “But can you look at the piece instead of always starting from scratch? Can you make those adjustments? It (revising) shows you can look at something critically and be willing to make those changes.”

Mr. Toth said that the format of the art classes themselves makes his role as a teacher slightly different. He explained how in the beginning of the year, he asks students questions about themselves. Then, they discuss what experiences have impacted their life outside of art. From there, Mr. Toth assigns open-ended art prompts that they “have to resolve in their own way.” For instance, he had students create 5×7 pieces that incorporated a thematic word that he selected, such as “assertive.”

“I use the analogy that I’m ‘sneaking vitamins’ into their food as their supplements,” Mr. Toth said. “Making artwork is a numbers game, so the more work that you make, the more failures that you go through, (and) the better that your work becomes.”

Additionally, while students would have points deducted for not completing all of the questions in standard AP exams, the art teachers strongly encourage students to submit their unfinished works in their portfolios.

“In any art, the process (is important),” Mrs. Ramos said. “You might not finish something, but if it conceptually takes you to the next place that you need to go to so you can better focus your idea, (then) they want to see that development. It’s great that they (The College Board) will accept that.”

Judging art on a rigid one-to-five scale is an approach that Mr. Armetta does not fully agree with, acknowledging that making the classes standardized has its drawbacks. He explained that it could lead to students conforming to a certain type of art or deciding that one piece is “good” and one is “bad” when basing scores off of a stricter rubric. However, he believes that positive changes can be made to the program.

“If there was perhaps a section of it (the AP art exams) that said, ‘Demonstrate two-point perspective,’ or ‘Demonstrate proportion’ (to show) that you understand it in a more academic way, (that could help),” Mr. Armetta said. “People could know what to aim for in a more concrete way without the pitfalls of it being so objective that it doesn’t have the subjectivity that is inherent in art.”

As Mr. Armetta illustrated, trying to implement rigid standards within AP art classes draws an expansive gray area as they quantify artistic expression. Even when students like Shea achieve perfect scores by demonstrating the caliber of their work through their portfolios, it raises the question of whether flawlessness is truly attainable in classes like these. And while teachers and students continue to debate these questions, in the end, Mrs. Ramos said that her goal of encouraging students to enjoy their artistic journeys remains constant.

“AP-3D, and AP classes broadly, have a really unique setting to make artwork,” Mrs. Ramos said. “It’s intense. You have to make a lot of art, and when you finish that process as a student, I feel that it can be really impressive to look back at all the work you did in just a few months. You almost realize what you’re capable of. Even if you don’t get the score you want (…), the process is still important, so I don’t think any of that (effort) is ever wasted.”