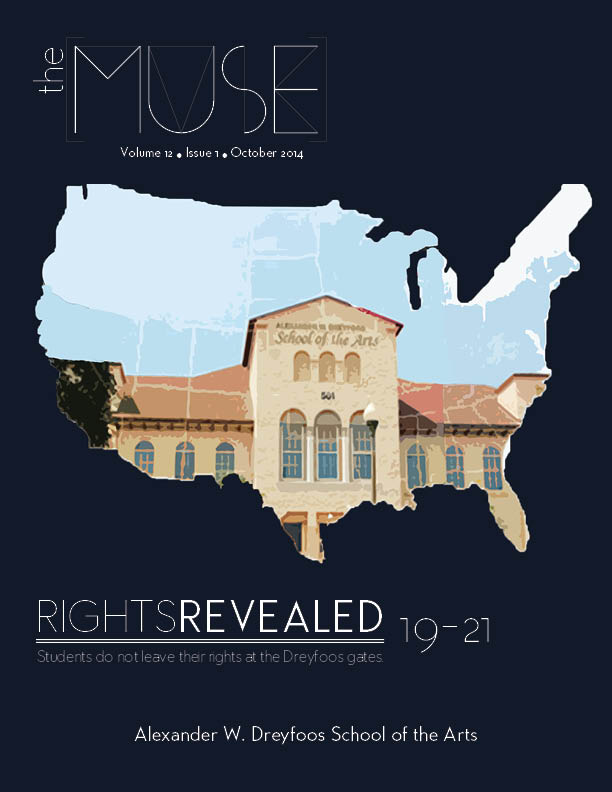

A student clutches her purse closely as she rushes through the halls. She has yearbook money and doesn’t want to lose it. A teacher notices and deems it suspicious. He stops her under the pretense of a random search. The student panics at the thought of him rummaging through her personal items. She wants to refuse. How should she respond?

A young woman transitions into a young man and changes his name accordingly. Despite this, his teacher insists on calling him by his given name. The action makes him uncomfortable. He wants to correct her, but fears he doesn’t have the right. Who can he go to?

A boy is pulled out of class and scolded for missing his detention. He tries to explain he could either attend detention or catch his bus. His teacher accuses of him of making excuses and gives him a suspension. He doesn’t believe he deserves it, but doesn’t know how to fight it. What can he do?

“I don’t think schools do a very good job of educating students on what their rights are and why they’re important,” Professor Mark Goodman, a medial law professor at Kent University said.

Knowing your rights can be the difference between incarceration and compensation. Students have the right to appeal suspensions, to refuse participation in a search, however to exercise those rights students first need to know and understand them. It’s vital for students to know their rights if they want to use and protect them. Here are the top five to know.

Search and Seizure: “Personal” Property

In 1985, the laws for search and seizure were established when an assistant principal caught a freshman in New Jersey smoking in the bathroom. The freshman, known anonymously as T.L.O., was brought to the principal’s office and denied the accusation. The principal ordered a search of her purse that revealed cigarettes, rolling papers, plastic bags, a large sum of money, marijuana, a list of those in debt to her and letters implicating the student as a drug dealer. T.L.O. was expelled and fined $100 by the school. She sued the school in protest, declaring the search was an invasion of her privacy.

The Supreme Court ruled a students’ personal property could be searched, but only with a reasonable suspicion by administration to do so. The vagueness of the term “reasonable” is still debated today. In T.L.O.’s case, when the principal searched for cigarettes, the rolling papers were in plain view. The papers are strongly associated with marijuana, so the principal had reasonable suspicion to continue searching T.L.O.’s bag.

The court ruling for school search and seizure contrasted with private property search and seizure laws of citizens, where not only is a warrant needed, but the police must be searching for specific evidence. Whereas the school administration can search by reasonable suspicion, police officers in the school need probable cause.

“An example of probable cause is if I see someone rolling a joint,” Officer James O’Sullivan said. “I see it, I smell it. I can go up to them and say ‘Can I see what you have in your pocket?’ Now if something is in a locked case, I don’t have the right.”

Probable cause also requires O’Sullivan to be searching for a specific piece of evidence, like a weapon.

“If [I’m searching for a weapon], I’m allowed to tap the pockets,” O’Sullivan said. “Now, if I’m called for a robbery and I’m tapping pockets, I’m only searching for a weapon. But if I tap and find a bag of marijuana, I don’t have the right to go and pull [the marijuana] out. I’m not looking for that, I’m looking for a gun.”

In case of a search and seizure by a school official, students reserve the right to refuse to be searched until provided with a reason for the search and evidence against them. If Officer O’Sullivan requests a search, the student should ask what he is searching for, and why the search is being conducted.

As for lockers, they are subject to search with reasonable suspicion by administration as well. The School District of Palm Beach County handbook states there should be signs posted explaining this to students. Moreover, if a school official questions and suspects a student of a crime, the student reserves the right to refuse to answer.

Censorship in Print and Speech

Students reserve the right to publish, and say, almost anything, as long as it is truthful. The spreading of hurtful lies in publication (libel) or by mouth (slander) are federal offenses.

That being said, students have the right to pedal publications of their own making through the school, such as pamphlets and fliers, given that they will not disrupt the learning environment schools strive to provide.

“It’s true [students] cannot express themselves in ways that will cause a substantial disruption,” Goodman said. “But that usually means a physical invasion. The school will frequently try to interfere with the students’ right to speak freely, but students usually have the right to [speak].”

The student has the right to speak freely, as any other citizen may, as long as their message does not detract from the educational system.

“The right I believe is most important is to raise questions and speak out,” Goodman said. “To engage and debate, within their school and outside it, about manners that concern their environment.”

LGBTQ Rights

All students have the right to be treated equally regardless of sexual preference or gender identity. Students have the right to be “out” on campus, and the right to keep their sexuality private. Teachers are not allowed to forcibly “out” students. Likewise, students have the right to bring up LGBTQ issues on campus, and access information on computers about these issues. Same-sex couples may attend prom. Bias on the issue of LGBTQ rights is not allowed in the classroom, and teachers should not be afraid to bring it up.

The Alliance, the LGBTQ support club, has met little resistance by administration since its formation last year.

“Administration was on board with [the Alliance],” English teacher Martha Warwick said.

The Alliance provides an open environment for students to discuss the struggles they face and how they can help one another. The club offers an unconditional acceptance that some students may not find elsewhere.

“I think it gives them a safe place to come and talk about issues,” Ms. Warwick said. “[Especially] If they haven’t come out to their parents because they don’t think they would approve.”

Off Campus Punishment

Can a student be punished for actions that didn’t occur on campus? The jury is still out on this one.

In 2012, two teenage girls from Santaluces High School made a video showcasing their racist comments about other students at the school. Their video was aimed at black students specifically, and taunted them over “how ghetto they are” and the use of “weaves”, before ending with a cheerful, “Peace and love!”

The girls were punished for their actions by the school, but due to being minors, many of the details were kept secret from the press.

“Punishing students off campus for expression they engage in exclusively outside of school [is a hot issue right now],” Professor Kent said. “The courts are in disagreement about that. Some say they have authority, others say they have none and the responsibility lies on the police, parents and the community.”

With the package deal that is technology and cyberbullying, this is an issue that will have to be explained. It is becoming easier and easier for the problems created off campus to follow students on campus.

“[Punishing a student off-campus is] a parent’s responsibility,” assistant principal George Miller said.

In the case of the Santaluces students, there were cries from the public to have the two tried for a hate crime that went unanswered. The girls did not go to court to appeal whatever punishment was dealt to them by the school.

Appealing Punishments

In the School District of Palm Beach County Handbook, students maintain the right to appeal to the school district and principal if they feel their punishment, specifically in the cases of suspension or expulsion, is unjustified.

The results of a successful appeal could be removal of the punishment from the students records or a repeal of the action altogether. T.L.O, for example, exercised this right, albeit unsuccessfully. But in the case of the Santaluces girls, there was no case and no law established.

Most of these rights provide freedom given “the learning environment is not disrupted.” At the end of the day, student rights are still protecting the work of a student, a scholar with the right to learn.